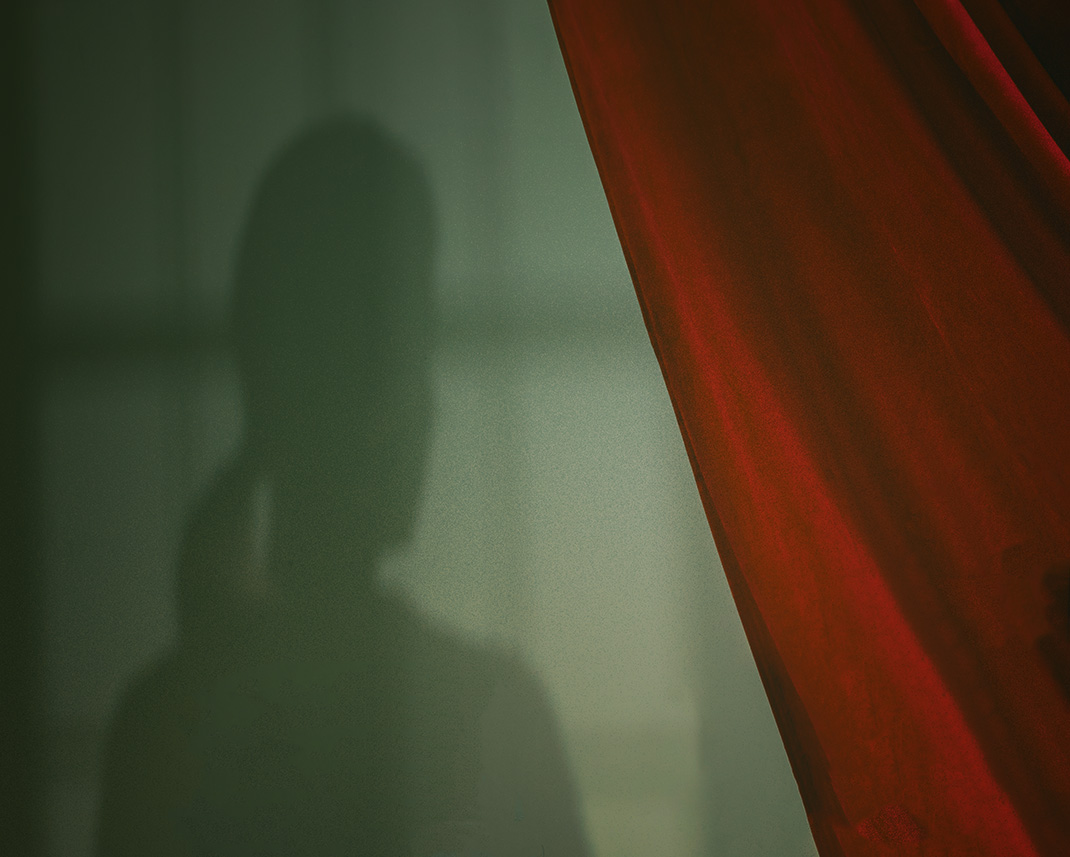

Even as the “New People Shaping Our Future” present fresh avenues forward from the pandemic, the shadow of a ninth entity stalks them. The phantom in reference? Disinformation.

In his book, This is Not Propaganda, Peter Pomerantsev presciently described the ability of disinformation to confuse and lull a populace into complacency. Who benefits when a society is collectively disoriented? When millions of followers of grassroots-generated misinformation are allowed to thrive on social media? When people lose a shared sense of what is real and what is right? Disconcertingly, the answer to “Who benefits?” isn’t “No one.” It is those with nefarious intentions, whether they be home-grown aspiring autocrats, external geopolitical rivals, a malicious individual or collective actors. We are all — private citizens, businesses, and society as a whole — vulnerable to the evils that can arise. As such, it is incumbent upon corporate leadership to play an active role in monitoring, understanding, and actively combatting disinformation. It’s not only the right thing to do, but also serves the self-interest of firms to shield against a severe and looming risk.

In our research, a disturbingly high percentage of respondents reported believing outlandish narratives. They ranged from the Covid-19 vaccine containing a microchip allowing the government to track recipients to the notion that John F. Kennedy Jr. would rise from the dead and personally reinstate Donald Trump as President. Those who believe these ideas are not a separate, stand-alone group — they intersect with the “New People Shaping Our Future.” There are members of the Virtual Natives, New Collars, and Digital Bloomers who are all convinced by blatant untruths.

To differing extents, we are all parts of the problem and we are all victims.

The disinformed are all of us.

People agree disinformation is a problem, but few think it impacts them personally. In our data, we observed that those with the greatest humility regarding their ability to separate truth from spin tended to be the least disinformed, while those with the highest confidence in their powers of discernment (believing, for example, that they already know which sources are “fake news” or that misinformation techniques don’t work on them) were actually at the highest risk. This effect may come from a greater willingness to put in the work of critical thinking on the part of those who approach information sources with a sense of humility. Those least likely to fall prey take the risks posed by disinformation most seriously, expect to come across information that calls for a skeptical eye in the normal course of their reading or browsing, and believe it takes both effort and skill to understand which sources are credible.

What best practices can others take from the most humble and least disinformed group we studied, the Climate Catalysts? They are the most likely, of any of our personas, to check the sources for information, read articles in depth instead of just skimming, and get information from peer-reviewed research journals, government entities, and subject-matter experts or independent thought leaders. From their experience with climate change, they have learned a measured, evidence-based approach, and apply it to the information they intake online.

Compounding the problem of hubris are the echo chambers generated by our modern information ecosystem. Individuals deliberately avoid high-quality information sources because of the uncomfortable cognitive dissonance that can result from having their core beliefs challenged. Many opt for “news” delivered via social media (which of course is highly personally targeted, reflecting back one’s own starting worldview), and from specific commercial news organizations, which increasingly may be doing the same. The selection of these comfortable, worldview-reaffirming sources comes at the expense of other potential information sources, such as government entities, subject-matter experts, and peer-reviewed journals, which would provide a broader diversity of perspectives.

We know definitively from observational studies of media consumption that many people use social media to get information. Yet, in our polling data, “social media” did not surface within the top four sources claimed by respondents. Our interpretation of this discrepancy is that when respondents read a story or watch a video clip created by a national or local media company but pushed to them via social media, they think of themselves as consuming the “real,” unfiltered news produced by journalists, and are not thinking about the role the platform serving them links plays in curating and targeting what they see. This leaves many oblivious to the fact that their daily drip-feed of information may not be “objective” after all.

Friends and family also compound the network effect, with many respondents exchanging information with their close contacts, which was the third-most popular news source globally. Since close contacts such as friends and family typically hold similar views, this information conduit further reinforces the phenomenon of isolated societal pockets – internally homogeneous but externally heterogeneous – that amplify specific beliefs by continually reflecting rather than challenging them. In short, echo chambers may influence people to distrust viewpoints that don’t fit their beliefs while believing the mistruths that do.

Unfortunately, our data finds that most people do not try to break out of these echo chambers. They generally do not look for new sources of information. They often do not check secondary sources before sharing news. And they mostly skim news rather than read in detail. People say they read diverse views and question the news they read, but their actions speak louder than their words, showing that most of us are not doing the tedious work needed to solicit reputable and diverse information.

In an age of constant information overload, skimming has become the norm. In every country surveyed, over 80% of people said they sometimes, often, or always skimmed articles.

In the US, Germany, France, UK, and Canada, about two-thirds of people said they did not check another source before sharing articles on social media. Brazil and Mexico were most responsible, with over half saying they often or always checked a second source before sharing articles on social media.

One way these dangers are mitigated is by people simply questioning what they are reading. People in Brazil, Mexico, the US, and France said they questioned what they read most, while Chinese and Germans questioned the least.

Although disinformation affects us all, it has undoubtedly hooked some more than others. This may be due to the addictive quality of emotionally engaging content, conspiracy theories, and the ecosystems in which they exist. Our data show that if someone believes one conspiracy, they are more likely to believe others. Those that believe Covid is a hoax, for example, reported believing in related statements at a much higher rate. They were especially likely to believe other theories related to Covid, such as the vaccine having a microchip. These correlations likely also point to the role of actors within the information ecosystem who are able to identify individuals getting drawn into a certain theory or set of beliefs based on their browsing behaviors, and feeding them more such information, sending them down further rabbit holes of outrage and illusion.

Beliefs in topics most related to misinformation were highest generally in the US, and lowest in Italy, Canada, and Germany. Interestingly, only one global question garnered the agreement of over half of respondents. In China, 57% of people said they generally agreed with the statement that Covid was created and released on purpose.

About two-thirds of our respondents said they could quickly spot fake news, but only half said they had actual techniques they employed for this purpose. A third said they had learned how to spot fake news growing up, which, based on how many reported falling for fake news, seems to be not nearly enough. An important tool going forward will be for businesses and governments to take a more active role in helping consumers within the information economy learn to consume wisely, better discern what is real from what is not, and think twice before they share.

Countries most confident in their ability to spot fake news quickly were Brazil, Italy, and the United States. However, that confidence did not consistently correlate with being educated in how to spot fake news in childhood. This may suggest that those taught to identify fake news in their childhood understand the challenge they face, and are wary to project confidence.

Trust has eroded in traditional information conduits. More people distrust than trust local and national governments, mainstream news, and social media. In this environment, businesses may be the last line of defense, and people expect them to step up. An unfortunate reality is that many of the topics around which disinformation tends to spring up have been heavily politicized. Companies therefore may fear taking a stand, for fear that it can be seen as taking sides politically, something that most brands would like to avoid for fear of alienating customers.

Despite the challenges of doing so, it is critical that brands and employers — not only media and information companies, but all organizations — take a stand in favor of truth and against disinformation, continuously calling out both truths and untruths as we see them. The fate of our world may very well depend on it.

As disinformation continues to disrupt and threaten life as we know it: