By John Romeo

I came of age with the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the rise of globalization, which makes the profound reversal of the last decade all the more striking. Competition is out, industrial policy is in. Economic tools are being weaponized. The big fiscal concerns are centered on advanced economies, not emerging markets. Government interference is the No. 1 concern of chief executives in our annual CEO survey.

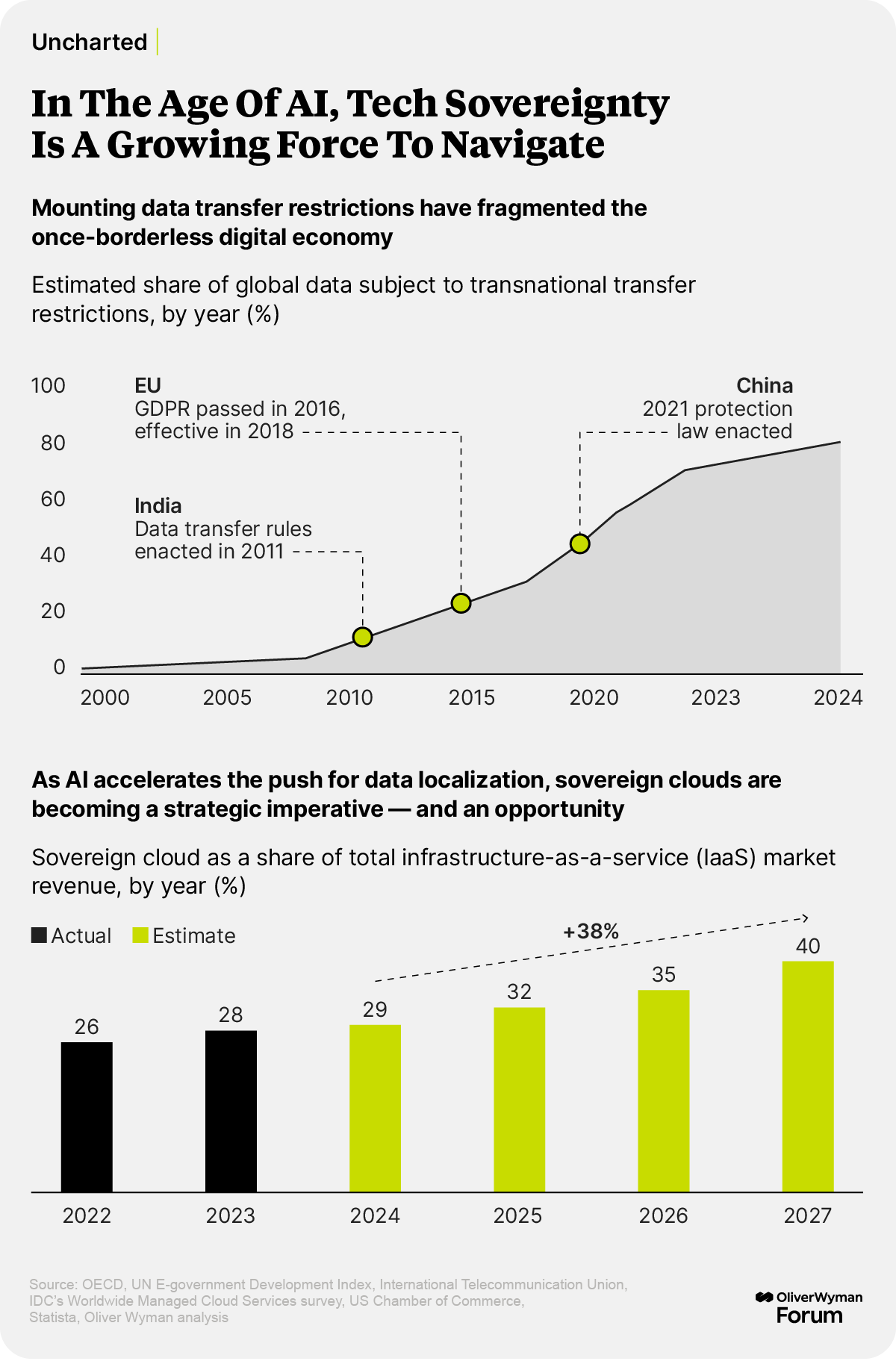

We see this dramatically in the drive for technological sovereignty. Over 80% of global data now face transnational transfer restrictions, a trend that’s likely to intensify as artificial intelligence takes hold. The old world order, built for postwar peace through collaboration and trade, is not suited to a world of protectionism, tech competition, and algorithmic chaos.

Much has been written about the need for business leaders and policymakers to balance efficiency with supply resilience. That is sensible, but what I find striking is the gap in trust. Trust is the essential underlying ingredient of leadership, the basis on which everything is built. The role of leaders is to build trust because without it everything collapses.

At the micro level of an individual company, trust seems more important than ever. But at the macro level of governments and multilateral institutions, trust is collapsing. Forget values, it’s now about winners and losers, about power. Foreign policy has become more promiscuous than ever: Prisoner’s dilemma on a grand scale, where countries hesitate to cooperate even where it’s in their best interests to do so. Is this gap in trust the real recession of our time?

Business is the most trusted institution, according to the latest Edelman Trust Barometer, with 62% of respondents to the firm’s 28-country survey voicing trust in the sector compared with 52% for government and the media. But trust in business fell slightly in 2025, suggesting the sector isn’t immune to broader trends. It can be tempting for business leaders to block out the external noise, keep their heads down, and focus on what they can control directly. But that leaves a gaping hole.

Business leaders have a responsibility to build trust — with employees, customers, suppliers, and the communities in which they operate. That means being transparent, delivering value and innovation, creating jobs and enhancing skills, and acting as a good corporate citizen. Just like a market can’t work without trust, neither can a company. In fact, such actions can enhance a company’s reputation in times of distrust and set a useful example for others to follow.

In the turbulent 1960s, the late US Senator Robert F. Kennedy said, “The future is not a gift. It is an achievement. Every generation helps make its own future. This is the essential challenge of the present.”

The same could be said today. The world may be unpredictable, but business leaders have agency and, I’d argue, a responsibility to shape the world we want to live in. Let’s not stack the deck against ourselves by allowing trust to erode any further.

John Romeo is CEO of the Oliver Wyman Forum

The world’s asset and wealth managers face an irony of riches: Never has there been so much money to manage, yet the pressure for consolidation is growing ever more intense. Firms that want to survive and thrive need to consider mergers and acquisitions as a core element of their strategy.

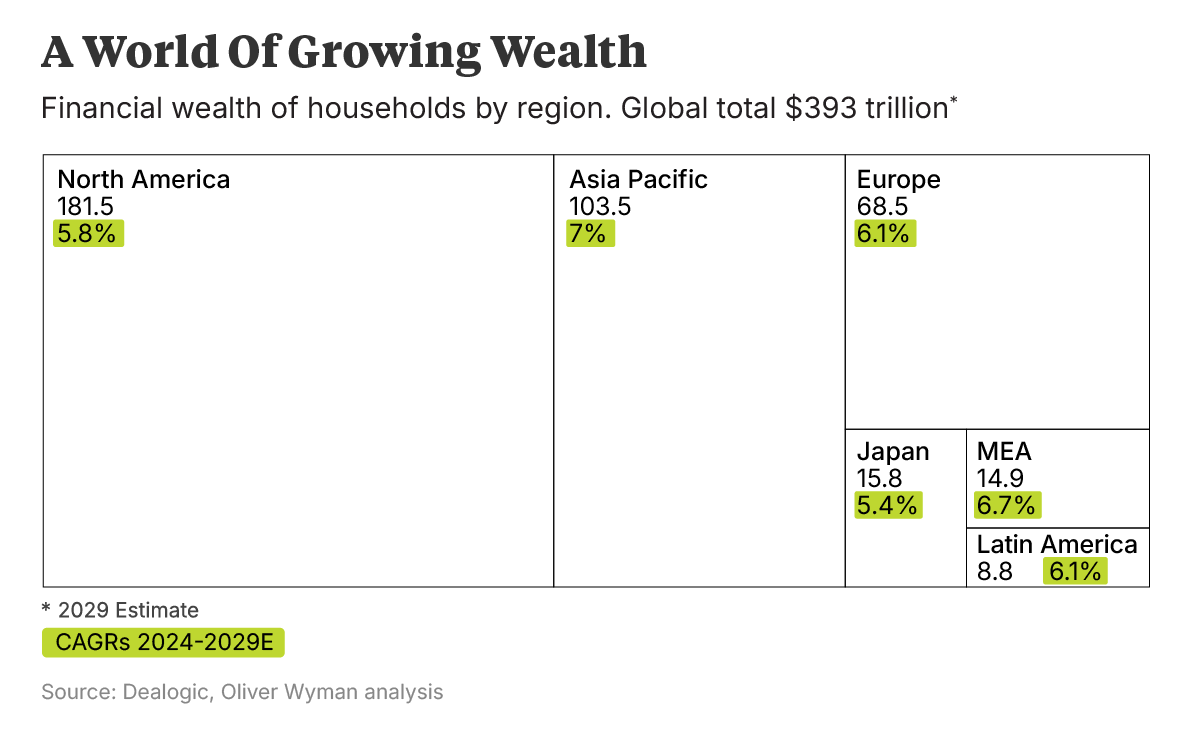

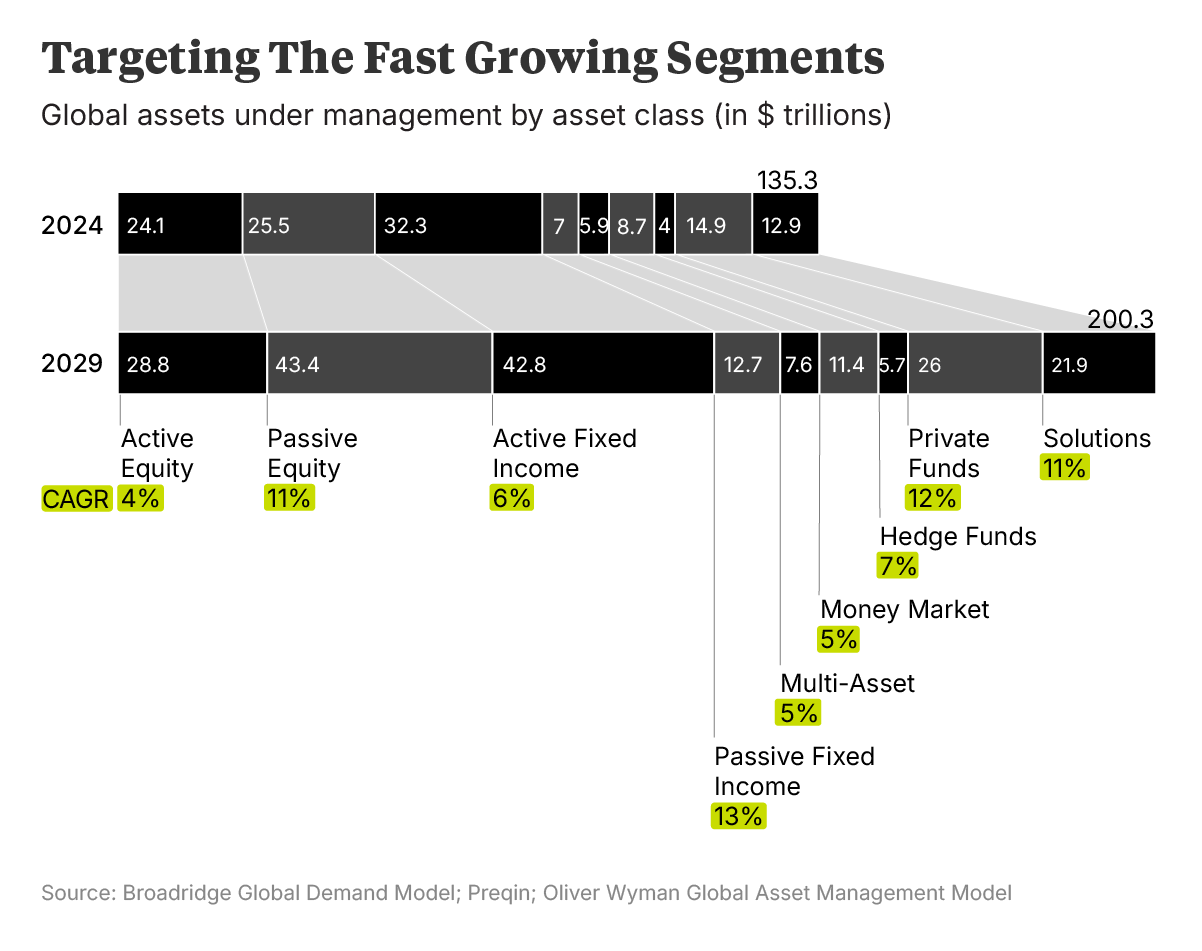

Global assets under management rose 13% in 2024 to a record $135 trillion — that’s 20% greater than world GDP! — and they are projected to hit $200 trillion by 2029, according to the latest annual report from Oliver Wyman and Morgan Stanley. The industry is surfing on a rising tide of money, with global household wealth seen growing at a 5.5% annual rate to reach $393 trillion in 2029.

Yet the rising cost of technology and artificial intelligence needed to stay competitive, the continued shift from actively managed portfolios to passive index trackers, and the advantages of scale in growth areas like private markets are likely to produce a big shakeout, particularly among mid-sized players. An acceleration of M&A activity is projected to involve over 1,500 significant transactions and shrink the ranks of asset and wealth management firms by 20% by 2029.

The shape and performance of the asset management industry is critically important for the health of the broader economy. Most people depend on industry firms to safeguard and grow their investments, and provide for their retirement, while innovation in growth areas like private capital provides an increasing share of finance for companies.

The new drivers of M&A

Consolidation has been taking place for years in the industry. Most mergers have been in-sector plays or involved traditional asset managers acquiring alternatives like hedge funds or private assets. Success has been elusive for many, though, with a majority of deals failing to boost margins or attract net inflows of investor funds.

The new wave of dealmaking will be propelled by the search for one or more of the four “Cs”: Cost synergies, new client segments or geographies, new capabilities, and access to seed or permanent capital. These transactions increasingly will occur across market segments, with players like insurance companies, for example, selling their asset management operations or entering joint ventures with partners that bring wider capabilities, client relationships, and technology to the table.

In effect, firms are evolving to go where the money and the margins are. Passive vehicles like low-cost index or exchange-traded funds now account for a majority of the world’s managed equity assets for the first time, having overtaken the stock pickers who traditionally dominated the industry. That is pushing firms to seek greater scale and invest in capabilities and relationships to expand in lucrative growth areas like private funds and wealth management for high-net-worth clients.

In another first, the industry now manages more assets on behalf of retail clients than institutions like pension funds or insurers. Those retail funds increasingly are managed in a more institutional style, though, with nearly two-thirds held in so-called solutions such as model portfolios, target-date funds, and funds of funds rather than traditional vehicles like mutual funds. Leading players are investing in such solutions, which along with private market funds are projected to grow at double-digit annual rates through 2029, roughly twice the pace of conventional asset classes.

A playbook for successful M&A

To get ahead in the new environment, acquisitive asset managers will need to assess their targets carefully. Rather than prioritizing cost-cutting, they should look for firms with complementary strengths in terms of their client base and product mix, as well as compatible cultures, an often-underestimated factor of success.

Buyers should de-risk transactions with measures like long-term investment agreements and retention bonuses to minimize the risk of losing assets and skilled managers. They also need to carry out a flawless post-merger integration that combines clear vision with ruthless execution on cost and synergy initiatives to achieve ambitious return targets.

Innovation is having a moment. We see it in the surging valuations of the Magnificent Seven tech stocks, the trillions of dollars companies are projected to spend on artificial intelligence infrastructure, and the awarding of the Nobel Prize to three economists for showing how new ideas drive technological progress and growth.

But just like the wealth it creates, innovation isn’t shared widely enough. This is keenly felt in the European Union, which is forecast to grow by just 1% this year and 1.7% in 2026, among the lowest rates of advanced economies, according to the International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook.

What Europe needs is a compelling vision for unleashing innovation and driving competitiveness, something the EU, its 27 member states, and the private sector can rally around and energize, according to senior business executives and policymakers at a conference on Financing For Growth, hosted in October by the Oliver Wyman Forum and the Centre for International Governance Innovation.

That vision should make competitiveness a paramount objective and identify the growth areas policymakers intend to prioritize, whether that’s defense, digital infrastructure and artificial intelligence, or renewable energy. As one participant said, “We need to make sure everybody knows where we want to invest, why we want to invest, why people should invest in Europe.”

Policymakers also need to streamline regulation to unlock the financing for economic transformation. Giving regulators a competition and capital formation mandate, similar to what the Bank of England has, would encourage a more risk-based approach that fosters innovation. In addition, governments should remove barriers to create a single market for savings and investment. That would give consumers more investing options and deepen EU capital markets so successful startups can scale their businesses in Europe rather than relocating to the US market.

Finally, Europe must develop a stronger risk-taking culture. Increased investment in education and mentorships is part of the solution. European institutions also could make a concerted effort to attract talent from abroad. Silicon Valley has a generation of entrepreneurs whose experience, networks, and wealth could boost any European country that manages to lure them.

Joel Mokyr, who shared the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics, argued that ideas that create entirely new products and solutions, not incremental change, are the real drivers of growth and prosperity. “Economic change depends, more than most economists think, on what people believe,” Mokyr wrote in his history of the British industrial revolution, “The Enlightened Economy.”

It’s time for Europe to put belief into practice.

A selection of smart reads on business, technology, geopolitics, culture, and beyond.

- Sanae Takaichi: 10 Things to Know About Japan’s Next Prime Minister. The woman set to become Japan’s first female prime minister is a conservative from a modest background, not a political scion; a mentee of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe; and a heavy metal fan who likes motorcycles.

- How GDP Hides Industrial Decline. Official statistics show that US manufacturing has never been higher, but a closer examination paints a different picture. The raw tonnage of steel produced by US mills declined by 18% between 1997 and 2023, for example, but adjustments for factors like inflation and quality improvements left the industry’s real value-added, which forms the basis of GDP calculations, up 125%.

- What Nobel Economics Prize Winners Teach Us About Growth. Policymakers should take a page from the works of Nobelists Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt, and seek to foster the discovery of new ideas, innovation, and technological progress to spur growth.

- How Mega Batteries Are Unlocking An Energy Revolution. A data and visually rich examination of the way in which a surge of battery storage is driving the growth of sustainable energy around the world.

- Jane Goodall, In Memoriam – What It Means To Be Human. In a conversation five years before her death, the British primatologist talks about the mother who encouraged her curiosity about nature; her personal empathy for chimpanzees, which was frowned upon by traditional science but critical to her discoveries about their behavior; and why she was busier than ever in her late 80s advocating for environmental activism.

Every month, we highlight key data points drawn from more than four years of consumer research.