Dr. Rebecca Katz has since been appointed to advise President-elect Biden's Transition COVID-19 Board.

The surging toll of the coronavirus has shocked the world, but it isn’t a surprise for Dr. Rebecca Katz and her colleagues at the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University Medical Center. For them, it was not a question of if, but when a new strain of influenza or a novel coronavirus would strike.

“We’ve been worried for a long time,” says Katz, who is a professor and director of the Center in Washington, D.C. “We’ve seen a fourfold increase in emerging infections during the last few decades, and not a single part of the world was spared.”

For years, Katz, who has been a consultant to the State Department on disease surveillance, has been pushing for a global effort to prevent these types of pandemics. The interest is now there, but that work will have to wait while the world scrambles to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. Georgetown has received so many requests for advice from US and global cities that — working with colleagues at the Nuclear Threat Initiative, the Center for Global Development, and Talus Analytics — it launched this week a new online tool, Covidlocal.org, to help guide authorities in their efforts to combat the virus. “We can’t look back now,” says Katz. “What we need to do now is mobilize the most aggressive response we’ve seen in our lives.”

Partha Bose, a partner at Oliver Wyman and a leader of the Oliver Wyman Forum, recently spoke with Katz and her colleague Matt Boyce, a senior research associate, about their work and what needs to be done to limit the spread of coronavirus, which has infected hundreds of thousands and claimed tens of thousands of lives since it first appeared in December in Wuhan, China.

Partha Bose: What is the focus of the Center?

Boyce: We conduct research to help develop tools that enable decision-makers to build sustained capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to health emergencies. We spend a lot of time thinking about how to prevent epidemics and pandemics and reduce biological risks. Cities are often on the front line of responding to these issues.

Thus far, our Center’s work in cities has primarily focused on advocacy and awareness-raising. We’ve been working with the Global Parliament of Mayors – who agreed in 2018 to prioritize developing capacity to confront infectious disease threats, and in 2019 set targets for increasing immunization and vaccination rates. One newer initiative is designed to help them assess the current state of capacity. Earlier this month, we released a self-assessment tool – the Rapid Urban Health Security Assessment (RUHSA) Tool – that allows for cities to evaluate their health preparedness. Our long-term goal is to develop this into an online tool and develop an index that would be open to the public.

Mayors could use our tool to baseline their current state of public health security and then report back each year how they may be performing against benchmarks.

Do mobility and artificial intelligence figure in the work you are doing?

Boyce: Both mobility and AI have played a role in this. All cities are extremely interconnected now, especially global cities. If a disease starts in one country, it goes to another because they are where the large airports and ports are. We need to do epidemiological modelling of how disease spreads in cities. Things like ride-sharing services and bike-sharing can affect how it spreads. And cities could use the AI tools we have now. You can collate thousands of data points and analyze them quickly. The public health department can look for unusual trends.

In much of the world, cities are leading the battle against coronavirus, often with varying levels of resources. What should they do?

Katz: We’ve seen roadmaps and things that have worked in other countries, but we have to adapt that for America. We’ve seen what is effective in China is a full lockdown of the entire society, paired with aggressive contact tracing and surveillance. We’ve also seen in South Korea and Singapore actions short of full lock downs, but still effective. That only works if it is started early and includes robust testing for coronavirus matched with the immediate identification of cases, as well as quarantine and individual monitoring.

The coronavirus already is widespread in many locations. What works then?

Katz: There is a roadmap. It is not an easy one. But we need to pair physical distancing with testing, isolation, contact tracing, and a resourced healthcare system.

America is diverse. Rural and urban localities have different levels of capacity as well as different threats. Many decision-makers want to know what the endgame looks like before they take aggressive actions, but they may have to take action without all of the answers.

People are sacrificing. They are staying home, they are teleworking if they can, but not all people are staying apart from each other. Because of this, the country needs a national, coordinated effort.

In the current pandemic, what worries you most?

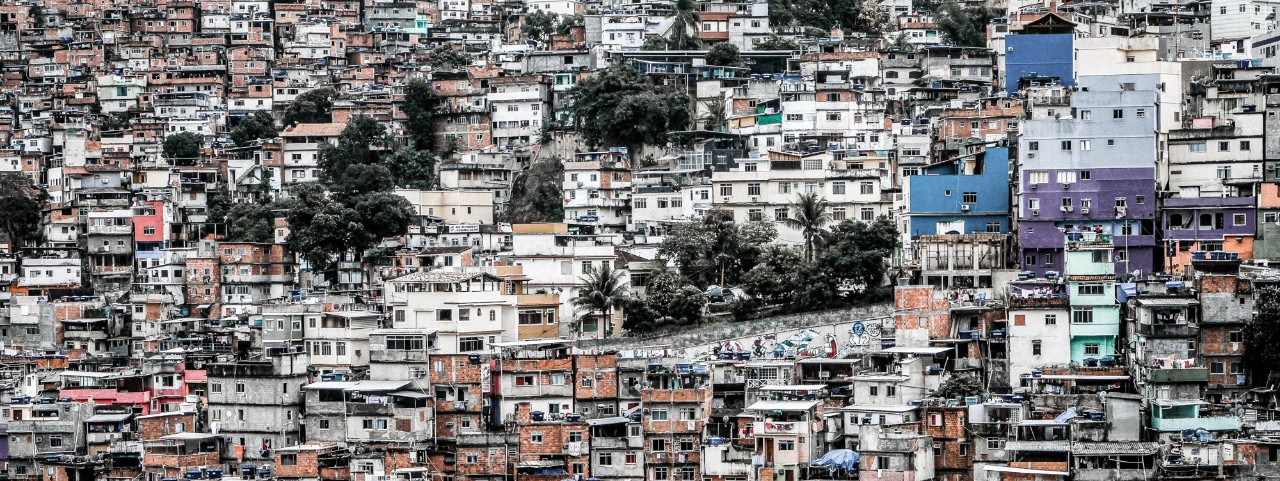

Boyce: The inequalities that exist in cities. The challenge is daunting in developed countries with well-developed health sectors. But how should it be addressed in homeless populations in these countries? Or, if the coronavirus reaches urban slums, those are powder kegs waiting to explode. People in slums may not have the option of social distancing or frequently washing their hands, so how can they protect themselves from becoming infected? It’s kind of terrifying and is going to take some creative solutions to slow down the spread of the virus.

How does governance affect how cities prepare for health crises?

Boyce: Although their specific powers and responsibilities may vary, generally speaking, mayors have some role in actively promoting and protecting the health of their population. But with limited resources, if you’re a mayor and are charged with fixing potholes or developing a disease-surveillance system, more often than not mayors will acknowledge the importance of the latter but prioritize the former. Still, developing public health capacities can be both examples of effective governance and a legacy item for city leadership.

Any other advice?

Boyce: I think cities should try to be open with their citizens. It helps to develop trust, which is fundamental for public health. They will be far better off for it. It will also be important for cities to learn from this. When this is all said and done, there will be a lot of lessons to be learned from this so that cities can make sure they are better prepared for future infectious disease outbreaks.

Is there anything to be hopeful about?

Katz: One of the positive things is every smart person in the country is focused on COVID because they can’t do anything else. I think there is going to be a lot of great innovation. I have no doubt we will have new ideas, particularly on the tech side.